Certified Farms

Al Fenaughty Orchards

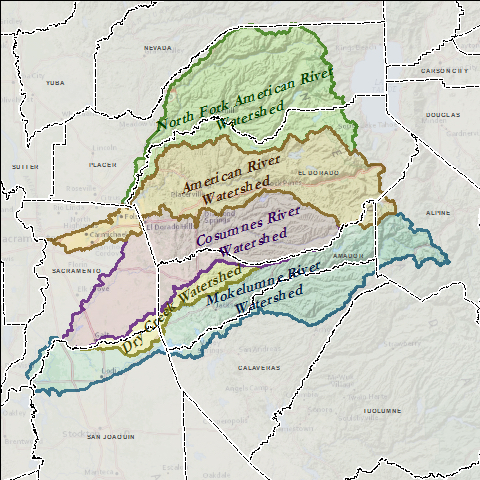

Related Watershed:

Website:

Andis Wines

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Anns Orchard

Related Watershed:

Website:

Arrastra Vineyard

Related Watershed:

Website:

Barsotti Ranch

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Batia Vineyards

Related Watershed:

Website:

Boeger Winery

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Boorinakis Harper Ranch

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Byecroft Road Vineyard

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

C.G. Di Arie Vineyard and Winery

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Cardanini's Vineyard & Pumpkin Patch

Related Watershed:

Website:

Carson Ridge Evergreens

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Caruso Family Vineyards

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Cedarville Vineyard

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Charles Spinetta Winery

Related Watershed:

Website:

Chateau Rodin Vineyards & Winery

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Christopherson Vineyard

Related Watershed:

Website:

Cielo Estate Winery

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Clos des Knolls Vineyard

Related Watershed:

Website:

Cooper Vineyard

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Cowan Family Farms

Related Watershed:

Website:

Crose Family Vineyard

Related Watershed:

Website:

Crystal Creek Tree Farm

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Crystal Springs Vineyard

Related Watershed:

Website:

D'Artagnan Vineyards

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Full Moon Farm

Related Watershed:

Website:

Goldbud Farms

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Green Valley Olive

Related Watershed:

Website:

Herbert Vineyard

Related Watershed:

Website:

Hinrichs Farm

Related Watershed:

Website:

Holly's Hill Vineyards, LLC

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

J & J Vineyards

Related Watershed:

Website:

Jack Russell Brewery & Winery

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

James Vineyards

Related Watershed:

James Vineyards in Hopland includes a wetland area and wildlife corridor set aside by owner Jim Nelson “just for the ducks”. This land is very plantable and its protection for wildlife demonstrates how individual farmers often put wildlife before profit. In 2007, James Vineyards received an award from Fish Friendly Farming recognizing Outstanding Efforts in Stream Habitat Improvement and Restoration.

Website:

Kingsgate Farm

Related Watershed:

Website:

La Chouette Vineyards

Related Watershed:

Website:

Latrobe Vineyards

Related Watershed:

Website:

Lava Cap Vineyards and Winery

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Linsteadt Vineyard LLC

Related Watershed:

Website:

Mad Dog Mesa

Related Watershed:

Website:

Madrona Vineyards

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Mandarin Hill Orchards

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

McGee Christmas Tree Farm

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Meadow View Gardens

Related Watershed:

Website:

Meyer Ranch

Related Watershed:

Website:

Miraflores Vineyard and Winery

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Musso Family Vineyard

Related Watershed:

Website:

Naked Vine Vineyards

Related Watershed:

Website:

Naylor Vineyard

Related Watershed:

Website:

Otow Orchard

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Pescatore Vineyard and Winery

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Pine Hill Orchard

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Ponderosa FFA School Farm

Related Watershed:

Website:

Potter Vineyards Inc

Related Watershed:

Website:

Quartz Hill Vineyard

Related Watershed:

Website:

Ranalli Vineyard at Lands End Ranch

Related Watershed:

Website:

Rancho Olivo Vineyards

Related Watershed:

Website:

Rinaldi Vineyard

Related Watershed:

Website:

Rubidoux Ridge Vineyard

Related Watershed:

Website:

Safari Estate Vineyard

Related Watershed:

Website:

Saluti Cellars

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Saureel Vineyards & Orchard

Related Watershed:

Website:

Schaefer Vineyards

Related Watershed:

Website:

Shake Ridge Ranch

Related Watershed:

Website:

Side Hill Citrus

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Sierra Vista Vineyards and Winery

Related Watershed:

Website:

Site 1 Vineyard

Related Watershed:

Website:

Site 2 Vineyard

Related Watershed:

Website:

Skinner Fairplay Vineyard

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Skinner Rescue Vineyard

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Smokey Ridge Ranch

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Sobon Wine - Fiddletown Vineyard

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Sobon Wine - Jackson Valley Vineyards

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Sobon Wine - Shenandoah Vineyards

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Sobon Wine - Sobon Estate Winery and Vineyards

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Spinetta Family Vineyards

Related Watershed:

Website:

Starfield Vineyard

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Sumu Kaw/Enye

Related Watershed:

Website:

Sun Mountain Farm

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Sunset Ridge Mandarins

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Tudsbury Orchards

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Upcountry Ranch

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Vine Hill Vineyards

Related Watershed:

Website:

Walker Vineyard

Related Watershed:

Website:

Wild Roam

Related Watershed:

Website:

Willow Pond Farm

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Windwalker Vineyard & Winery

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Wofford Acres Vineyards

Related Watershed:

Winery:

Website:

Z & B Ranch

Related Watershed:

Website: